This was fine, and the results were very drinkable, but after a couple of years I yearned for something more interesting, because what I was making was really too wine-like. I certainly didn't want to go down the route towards vinegar, but I was looking for something more complex and distinctive in flavour terms. So I started to think about natural or semi-natural fermentations again, the sort of thing the UK cider industry was traditionally doing up to the 60's but which had since been lost by the march of the bean-counters, who tend to judge quality only by the 'bottom line'. Well that's fine if you've got to run a business and turn in a profit for your shareholders, but my cidermaking is a hobby, so I don't! I started to read the older Long Ashton literature, and thought about what the French cidermakers were doing, and decided to change direction. So now I'm going back to tradition for the most part, and the graph below helps to explain what I'm trying to do.

First

of all, note the timescale, from early October to the beginning of April.

Traditional cidermaking, like winemaking, is a seasonal and once-a-year

activity, very different from the brewing of beer. This is also very different

from the way that economics has dictated the structure of the modern cider

industry, where ciders have to be produced to meet supermarket demand in

as little as two weeks from juice (or concentrate) to bottled product!

First

of all, note the timescale, from early October to the beginning of April.

Traditional cidermaking, like winemaking, is a seasonal and once-a-year

activity, very different from the brewing of beer. This is also very different

from the way that economics has dictated the structure of the modern cider

industry, where ciders have to be produced to meet supermarket demand in

as little as two weeks from juice (or concentrate) to bottled product!

The four fermentation vats (FV1 to FV4) represent four different cidermaking styles as follows:

Because for 1997 I'd decided to forgo the added yeast, I added sulphur dioxide at 50 parts per million, topped the vat with an airlock….and waited. This is the traditional method for killing acetic acid bacteria and moulds and inhibiting most wild yeasts, while allowing beneficial fermenting yeasts (which are sulphite resistant) to multiply and begin the ferment. Sure enough, the first bubbles were seen after a fortnight, and by three weeks into the fermentation it was going well. The gravity drop continued until 14th December, when I was pressing all my mainstream bittersweet (low acid) fruit comprising Harry Masters Jersey, Yarlington Mill, Medaille d'Or, Sweet Alford and Dabinett. That pressing gave a juice of SG 1.055 (14 Brix ) but with a pH of 4.2 which is extremely low in acid. So I blended the existing FV1 part-made cider with an equal volume of juice from this latest pressing, which is why the SG on the graph shoots up at this point. The pH was now about 3.4 which is more acceptable.

I didn't of course need to add any more yeast or SO2, since the fermentation was already vigorous, and I just let it romp away steadily until the end of February when it was practically finished (SG 1.004). At this point I racked it off into a new 60 litre Graf tank which was then corked for storage, and the remainder was treated with 75 ppm sulphur dioxide and went into one-pint crown-capped bottles. By June these bottles had just a slight 'prickle' of CO2 as they're opened but were never intended to be fully sparkling - just a dry and slightly acid cider for drinking with a meal. The bulk cider will eventually be primed, when required, for dispensing from a 25 litre plastic pressure keg. If the residual yeast is dead by then, I shall need to add some fresh S. bayanus to develop the carbonation after addition of priming sugar.

I wanted to stop this with significant residual sugar and I've repeated

the plot here so you can see that I racked it on 24th January

(shown by the arrow) to slow it down. This removes nitrogenous nutrients

which are mostly tied up with the yeast and you can see that the SG flattens

off quite markedly after the racking. The same is true of FV3(in

the blue) which was another varietal blend of Stoke Red and

Dabinett (5:2) with an original SG of 1.056 but a slightly higher pH of

3.6 (due to the Dabinett which is low in acid). Because of the higher pH

I added more SO2 at 150 ppm (see

my Science of Cidermaking Part 3 for the 'official'

amounts to use!). I have no real idea why the fermentation profiles for

FV2 and FV3 were different, but at any rate by the end of March they had

both settled at SG 1.016 and SG 1.012 respectively. I bottled all of FV2

in glass crown-capped beer or champagne bottles, without SO2

in order to allow for a malo-lactic fermentation, and by June they were

sparkling very well when poured. My impression is that some have gone malo-lactic

and others not, but I haven't checked this by analysis yet. FV3 was finished

partly in a 25 litre plastic pressure dispensing keg (a 'King Keg' sold

for home brewing), and partly into two 12 litre stainless steel pressure

vessels (the sort that are used for dispensing carbonated drinks in bars).

The plastic keg I'm drinking now and, when this is empty, the pressure

vessels will be refrigerated for two days and then rapidly transferred

to

the plastic keg (to avoid loss of the natural carbonation). This should

take place quite soon (August) since the 'King Keg' is nearly empty and

I've enjoyed drinking it as an 'off-sweet' and nicely balanced cider. I

haven't been aware of an especially distinctive varietal character, however.

I wanted to stop this with significant residual sugar and I've repeated

the plot here so you can see that I racked it on 24th January

(shown by the arrow) to slow it down. This removes nitrogenous nutrients

which are mostly tied up with the yeast and you can see that the SG flattens

off quite markedly after the racking. The same is true of FV3(in

the blue) which was another varietal blend of Stoke Red and

Dabinett (5:2) with an original SG of 1.056 but a slightly higher pH of

3.6 (due to the Dabinett which is low in acid). Because of the higher pH

I added more SO2 at 150 ppm (see

my Science of Cidermaking Part 3 for the 'official'

amounts to use!). I have no real idea why the fermentation profiles for

FV2 and FV3 were different, but at any rate by the end of March they had

both settled at SG 1.016 and SG 1.012 respectively. I bottled all of FV2

in glass crown-capped beer or champagne bottles, without SO2

in order to allow for a malo-lactic fermentation, and by June they were

sparkling very well when poured. My impression is that some have gone malo-lactic

and others not, but I haven't checked this by analysis yet. FV3 was finished

partly in a 25 litre plastic pressure dispensing keg (a 'King Keg' sold

for home brewing), and partly into two 12 litre stainless steel pressure

vessels (the sort that are used for dispensing carbonated drinks in bars).

The plastic keg I'm drinking now and, when this is empty, the pressure

vessels will be refrigerated for two days and then rapidly transferred

to

the plastic keg (to avoid loss of the natural carbonation). This should

take place quite soon (August) since the 'King Keg' is nearly empty and

I've enjoyed drinking it as an 'off-sweet' and nicely balanced cider. I

haven't been aware of an especially distinctive varietal character, however.

Ideally, a pectin clot should form within a week, but in this case it

didn't. After two weeks, a significant amount of sludge had dropped to

the bottom but the 'chapeau brun' showed no sign of forming, although the

juice was becoming 'striated' with insoluble material - the beginnings

of what might form a clot. Ominously, odd specks of mould were beginning

to form on the juice surface. Previous experience has taught me that this

is a dangerous stage because any significant mould growth can taint the

cider irreversibly.

I therefore cut my losses

on 'true' keeving, racked the juice into a full tank with an air lock,

and fermentation had begun by the next weekend (27th December).

I therefore cut my losses

on 'true' keeving, racked the juice into a full tank with an air lock,

and fermentation had begun by the next weekend (27th December).

By 18th January a considerable amount of sludge had fallen to the bottom of the tank - some of this was in effect failed 'keeve' in addition to the normal yeast deposit. I therefore racked to remove the juice from the sludge and to slow things down. Because of the high pH the cider was sub-acid and not likely to be well-balanced. To correct this, and to help with microbial stability, I added enough malic acid on 1st March to raise the titratable acidity by 0.1%. Finally on 22nd March I racked and bottled it in crown-capped beer bottles. By June this cider was foaming when the bottle was opened - typically from this style of cider, the foam is stable for several seconds which can give difficulties and makes it advisable to pour it over a sink! The colour is darker orange than the other ciders I describe, due to the bittersweet content. The flavour, apart from being less acid, also has a distinct 'bittersweet' component to it, characterised by slightly 'smoky' or 'bacon-like' attributes. In this current batch, however, that is not so marked as I've had previously. Nor is there as significant a note of acetic acid / ethyl acetate as in some of my previous ciders of this type which were made without any sulphiting at the keeving stage (see below).

That's what happens when you stick your neck out and try the extremes, and it reminded me once again what a huge contribution sulphite and sulphur dioxide (originally in the form of sulphur candles) have made to reliable wine and cider making since medieval times. You might manage without them, and I have done, but it's tricky!

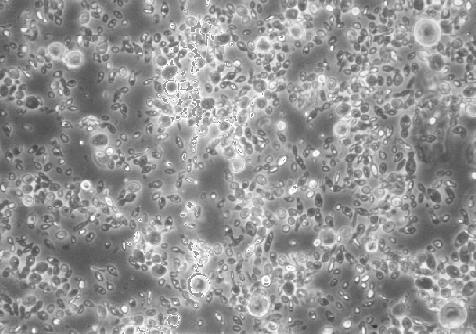

The picture here shows a yeast deposit from one of my previous 'natural' ciders. It's a pretty diverse collection of organisms! Look carefully and you can see small circular yeasts and slightly elongated forms - probably Saccharomyces. Some of these are 'budding' or are splitting in two via a 'septum'. Then there are the slightly larger 'lemon-shaped' forms which are the typical 'apiculate' yeasts mentioned above. These species are about 5 - 8 micrometres (microns) in size. Finally there are some much larger circular yeasts (up to 25 microns) which are almost certainly Saccharomycodes ludwigii . This is generally regarded as a spoilage yeast in cider factories, where the cider is pasteurised, since it slowly metabolises sugar and forms large clumps in the bottom of bottles - in unpasteurised naturally conditioned ciders such as mine it's probably just a normal component of the microflora and has to compete with all the other yeasts present too.

An old and respected colleague of mine, Professor Vernon Singleton,

now retired from the Oenology department at the University of California

at Davis, once finished a highly technical lecture I attended with the

reminder that "wine is for pleasure".

Cider too, I guess. What he was trying to convey was that for all our science and our knowledge the sole object of these beverages is to give people enjoyment - without that, they would have no purpose. Meanwhile here's a picture of my orchard on a frosty morning in winter - the dormant season but not necessarily an unattractive one!

Back to the previous 'Milling and Pressing' page

Back to my Cidermaking 'Contents' page

This page last updated 23 August 1998